ANALYSIS

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule soon on whether to overturn the Chevron doctrine, a landmark precedent that has stood for 40 years. Scrapping the doctrine could have major impacts on regulation in such areas as pollution, climate change, and endangered species.

What will it mean for policymaking on environmental and other issues, practically speaking, if the U.S. Supreme Court jettisons the Chevron doctrine?

This question is on the minds of legal observers and environmental advocates as they wait for the justices to decide two consolidated cases in which the court has been asked to overrule the famous precedent that has stood for four decades. That ruling, in the 1984 case Chevron v. National Resources Defense Council, says that where Congress has not expressed itself clearly, leaving gaps or ambiguities in federal statutes, agencies should be allowed to adopt the interpretation they prefer, so long as that interpretation is reasonable.

The cases now before the Supreme Court — Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless Inc. v. Department of Commerce — were brought by commercial fishing groups challenging a National Marine Fisheries Service rule, and a decision is expected in the coming weeks. If the court decides to scrap the Chevron doctrine, it could have major implications for environmental policymaking and regulation on issues ranging from air pollution and climate change to clean water rules, public lands management, endangered species protection, and more.

Overturning Chevron would reduce government’s ability to respond to new scientific findings and technological developments.

There are two very different perspectives on the Chevron doctrine, which largely determine whether one thinks it ought to be overruled. Critics say that Chevron gives policymaking discretion to unaccountable agency bureaucrats, allows presidents to abuse their executive authority, and encourages members of Congress to shirk their legislative responsibilities. They charge that Chevron is “reliance-destroying” because it allows policy “flip-flops” between administrations and that it cannot be squared with the landmark Marbury v. Madison decision, which ruled that courts “say what the law is” and established the principle of judicial review. If one believes that there is always a single best answer to how to interpret a given statutory provision, and that a skilled enough legal interpreter can always produce that best answer, then overturning Chevron has some intuitive appeal. Why ever defer to an agency when judges can just decide?

Supporters of Chevron contest each of these claims. Congress inevitably leaves certain interpretive question unresolved, they say, which means that some statutory provisions are capable of different understandings. And democratically elected presidents charged with executing the law are entitled to use this ambiguity to advance their policy preferences. (This is otherwise known as the “elections have consequences” argument.) They would note that agencies are amply accountable to multiple overseers and restricted by many legal, political, and institutional constraints. And they would reject the idea that Chevron is somehow responsible for legislative shirking or gridlock and point to House and Senate rules that make passing legislation exceedingly difficult, along with hyper-partisanship. While accepting that judicial review is legitimate and necessary, they would also say that nothing in the Constitution requires courts to decide all legal questions with no deference to expert regulators.

A fishing vessel in Cape May, New Jersey, named in the court case brought by fishing groups against a federal fisheries rule.

Rachel Wisniewski / Bloomberg via Getty Images

To the claim that there is one discernible “best” answer to every hard question of statutory interpretation, they would say no, sometimes Congress has not been clear (whether because political compromise requires some degree of unclarity; or because Congress is not prescient; or intentionally wishes to leave agencies room to adapt to change; or because of the limits of language), and there is more than one arguably best answer. From this point of view, Chevron is a sensible default rule of decision. It keeps courts from substituting their judgments for an agency’s — and that is how it should be, since the agency charged with day-to-day implementation will better know what is reasonable in the run-of-the-mill case.

I support the defense of Chevron, as my past writings have made clear. Overturning or enfeebling Chevron would have negative consequences. It would further concentrate power in the judiciary, reduce the government’s ability to respond to new scientific findings and technological developments, as well as to social and economic change; sow disruption and disorder in the lower courts; and undermine the regulatory stability on which the normal course of business depends. For example, courts rather than agencies would decide what pollution standards are “requisite to protect the public health” and allow for an “adequate margin of safety,” as the Environmental Protection Agency is mandated to do; what it means for an upwind state to “contribute significantly” to the failure of downwind states to meet national air quality standards under the Clean Air Act; and whether “harm” to an endangered species is limited to direct applications of force or can include habitat destruction.

If Chevron is abandoned, agencies will have to defend every interpretive choice as the single best way to read a statute.

First, overturning Chevron would shift substantial power to the judiciary to have the last word on many important questions of policy that arise under federal law. It is more democratic for interpretive decisions, which inevitably involve policy discretion, to be made by agencies — which are part of an executive branch headed by an elected president, and subject to ongoing oversight by Congress — rather than by unelected judges. Deciding what qualifies as the “best system of emission reduction” or whether implementing an offshore drilling plan would “probably cause serious harm or damage… to the marine, coastal or human environment” — as the Secretary of the Interior is authorized to do — depends on a combination of legal, factual, and policy determinations. Agencies have research- and information-gathering capacity, and relevant expertise in areas of regulatory complexity, that courts do not possess. They are also required to solicit, consider, and respond to comments on their regulatory proposals from industry and other stakeholders, including states. Companies and their trade associations can and do weigh in through this process to shape rules that affect them, and to require agencies to explain themselves.

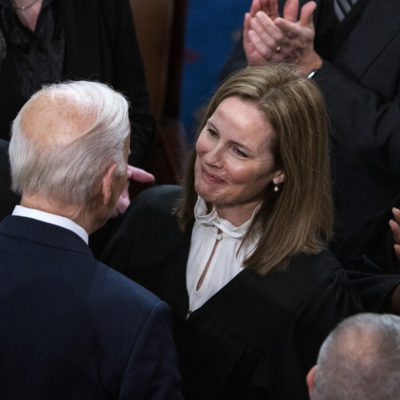

Justice Amy Coney Barrett has suggested overturning the Chevron doctrine could lead to a flood of litigation.

Tom Williams / CQ Roll Call via AP Images

Some of the conservative justices have implied that overturning Chevron is necessary to protect congressional prerogatives and restore Congress to its rightful role in our separation of powers scheme. Yet Congress already has the means to constrain agency overreach and check the president’s executive power. Under the Congressional Review Act, Congress has required agencies to provide advance notice of their rules and can effectively cancel any rule before it takes legal effect through a fast-track, filibuster-proof process requiring only a majority vote. Congress can also make its wishes known in the annual appropriations process and can defund agency initiatives of which it disapproves. If anything, abandoning Chevron would make the presumed separation of powers imbalance worse, not better — Congress could still use vague language to avoid making hard policy choices, only now those policy choices would be made by courts.

Second, without Chevron, it will be harder for agencies to adapt regulation to new circumstances, something we should want government to do. Under Chevron, agencies can consider the latest scientific advances and technology developments; re-examine costs and benefits; consult with stakeholders; and consider the president’s policy preferences too, knowing that the next administration may adopt a different view — in which case the agency would then bear the burden of explaining to the public and the courts why that new understanding is also reasonable. But without Chevron, agencies will have to defend every interpretive choice as the single best way to read the statute, not only now but for all time, making it more difficult for a later administration to change its mind given new information or unforeseen conditions. Eliminating flexibility will not improve regulation. It will rigidify it and prevent the government from updating policy over time.

Agency officials are more expert in regulatory implementation and more politically accountable than are federal judges.

Third, overturning Chevron is likely to inspire more litigation and instability in the lower courts. Releasing all federal judges from any obligation to defer to agencies will invite parties to challenge many more rules — not just the most significant ones — and relitigate thousands of interpretations that courts have already settled. Justice Amy Coney Barrett raised this concern at oral argument, when she suggested that a flood of litigation might ensue over longstanding interpretations, where courts already determined that Congress was not clear and deferred to agencies.

Overturning Chevron will also undermine uniformity and consistency in the interpretation of federal law. Chevron is a familiar and useful tool for lower court judges — they understand and know how to use its framework. What might replace it? The most likely standard of review the Supreme Court would substitute is so-called Skidmore deference, which is the amount of deference an agency is due in the estimation of the reviewing court based on several considerations — a standard that provides lower courts little guidance and maximum flexibility. As Justice Elena Kagan said at oral argument, “Skidmore has always meant nothing.” Without Chevron, judges will wade into often unfamiliar and technically complex statutes armed with their dictionaries, textualist principles, and canons of construction. They may or may not give any respect to the agency’s views. This situation cannot help but increase conflicts among the lower courts.

Haze hangs over lower Manhattan last July.

Gary Hershorn / Getty Images

This prospect leads to a fourth and related point, which is that overturning Chevron is likely to be bad for business. Of course, many conservative opponents of regulation believe that Chevron enables more regulation on balance, so they would like to see it gone. But there is a decent possibility that the consequences for business will be, at best, mixed. A few high-profile politically controversial rules will always wind up in the Supreme Court. And for those, Chevron will hardly matter because the Court will simply decide, as it has shown a tendency to do. But overall, Chevron is a stabilizing force because of its effect on lower courts. Without Chevron’s default presumption in favor of government, it will be more tempting for many would-be litigants — domestic and foreign companies, state attorneys general, public interest groups, other stakeholders — to challenge agency rules, even those that many, if not most, companies might be able to live with or which they might at least prefer to uncertainty. Unleashing a cacophony of inconsistent rulings on what various statutory provisions mean, issued by up to 850 federal judges with minimal expertise in technical areas undermines the stable conditions necessary for the private sector to thrive.

The Supreme Court may not overturn Chevron after all, perhaps in part because of some of these considerations. It may limit its application to narrow circumstances or impose new threshold tests on when it can apply. But it is highly unlikely simply to reaffirm it, which would be the best outcome for democracy, good governance, and business.

At bottom, Chevron embodies an inclination — that federal agencies ought to be given the benefit of the doubt if they offer good reasons for interpreting a statute a particular way, when no one can say for sure what Congress would have wanted to do. That inclination depends on a belief that agency officials are both more expert in regulatory implementation and more politically accountable than are federal judges, so that in such instances, agencies ought to be trusted to make the call. Coming to that conclusion requires judges to at least consider that there may be limits to their prowess and to allow that when it comes to complex regulatory statutes, where legal meaning and policy discretion are often intertwined, agencies can be legitimate legal interpreters. That attitude represents a certain faith in the capacity and competence of government that it would be a terrible shame to lose.