Kevin Lewis tells us: articleSince the 2016 U.S. presidential election, adverse infant health outcomes have increased among non-white U.S.-born and foreign-born mothers, according to a recent study published in the journal Demography. From the abstract:

Using data on 15,568,710 U.S. births between November 2012 and November 2018, we find increases in adverse birth outcomes among U.S.- and foreign-born mothers racialized as Black, Hispanic, and Asian Pacific Islander (API) after the election of Trump, compared with the period covering both terms of President Obama. Results for Whites suggest no changes or slight decreases in adverse outcomes after the election of Trump, but this finding is not robust to seasonality. Disparities in adverse birth outcomes between Black-White, Hispanic-White, and API-White mothers widened after the election of Trump for both U.S.- and foreign-born mothers. Our findings suggest that Trump’s election was associated with increased adverse birth outcomes among Black-White, Hispanic-White, and API-White mothers. racist and xenophobic [italics in the original] A macro-political event that has undermined the health of infants born to non-white mothers in the United States.

The political agenda is clear. So let’s look at the paper. We’ve been reading a lot about the public health crisis that’s happening among white men, so it seems reasonable that researchers should study what’s happening among nonwhite women.

There’s a saying that goes, “I read articles because you don’t have to,” but in my opinion, that’s nonsense.

I won’t go into the whole thing because that’s not the purpose of this article, but I’ll give you a little bit of a feel for things. There are two sets of raw data graphs in this paper, one showing low birth weight and one showing preterm birth. I’ll show preterm birth because the pattern is a little more dramatic.

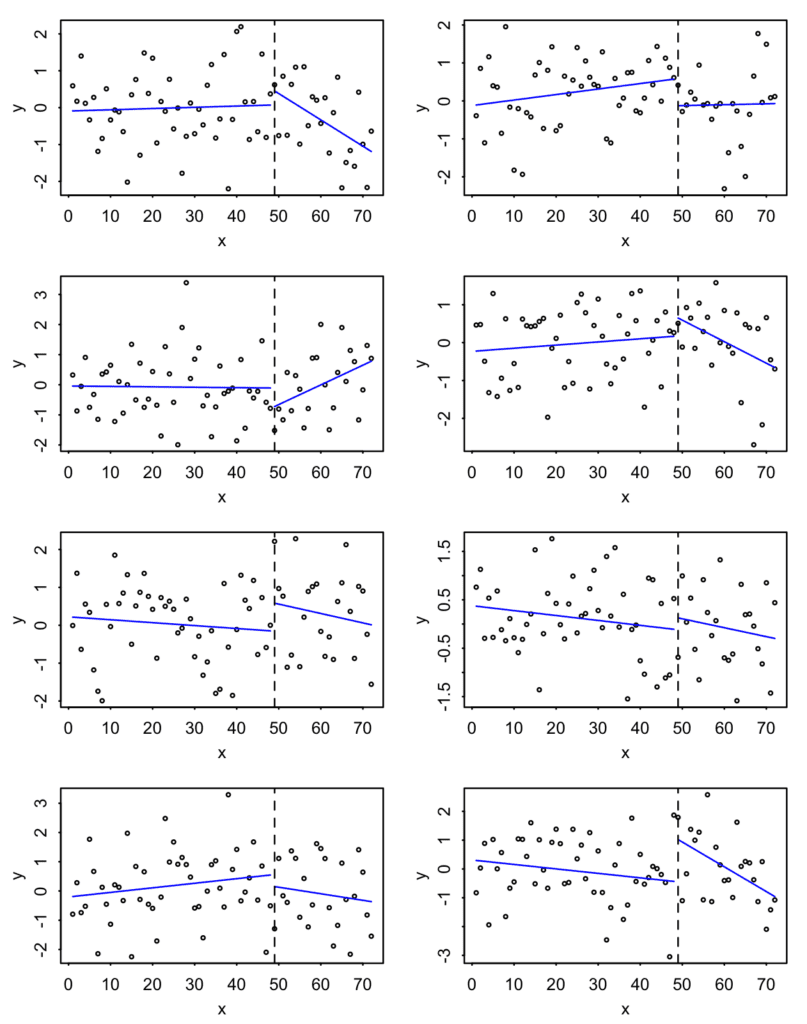

I have no idea about the weird y-axis labels or the line errors near the start of each custom time series, and the whole discontinuity is just nonsense. (a) If you pick a random time point and break the line, you’ll see that kind of pattern (ref. This paper is in collaboration with Zelizer (b) Given that these babies were conceived almost a year ago, there is no logical reason to think of November 2016 as some kind of turning point month. So this graph is just something someone did with some data.

Besides all that, there is the problem of how to interpret this graph. Here is what the paper explains:

Visual assessment of the data shows that all mothers experienced a trend change in adverse birth outcomes in November 2016. Consistent with the hypothesis of racial harm from Trump’s election, the election coincides with an increase in the slope of the trend line for all nonwhite mothers except U.S.-born API mothers. For example, among U.S.- and foreign-born Hispanic mothers, monthly preterm birth rates decreased in the period before Trump’s election but increased in the period after Trump’s election.

There’s so much wrong with that short paragraph. They’re making a lot of strong claims based on these very noisy slope estimates, and they seem to be trying really hard to push the narrative that something different is happening among non-whites, even though the general pattern is similar across all groups. Also, no, there’s no evidence in the graph that anything happened in November 2016. If you pick a different month, you’ll see different slopes and discontinuities. Well… let me show you with a simple simulation.

par(mfrow=c(4,2), mar=c(3,3,1,1), mgp=c(1.7,.5,0), tck=-.01)

T <- 72

x <- 1:T

before <- x < 48

for (k in 1:8){

y <- rnorm(T, 0, 1)

fit_before <- coef(lm(y ~ x, subset=before))

fit_after <- coef(lm(y ~ x, subset=!before))

plot(x, y, cex=.5)

curve(fit_before[1] + fit_before[2]*x, from=1, to=48, col="blue", add=TRUE)

curve(fit_after[1] + fit_after[2]*x, from=49, to=T, col="blue", add=TRUE)

abline(v=49, lty=2)

}

The data is completely random, but otherwise we do the same thing as we did in the graph above: we take a 6-year monthly time series and apply separate curves to the first 4 years and the last 2 years.

The results are as follows:

So, yes, there is a clear discontinuity wherever you divide the data. The main difference is that the graph in the published paper shows a similar trend across all eight groups. But that doesn’t support the claim that the change is “racialized.”

The authors could probably defend themselves against the above criticism by saying that what they discussed above is just a descriptive analysis and that the core of the paper is the regression model. However, their interpretation of the regression has the same problem of relying on the arbitrary discontinuity in November 2016 and picking and choosing different comparisons to tell the story they want to tell. For example, “For API and Hispanic mothers, Trump’s election was more detrimental to foreign-born mothers than to US-born mothers.” The estimates have standard errors, which I find largely meaningless in the context of all the unmodeled trends in the data. They briefly mention it on page 20, but don’t really think much about the impact on all the previously reported results.

I don’t think the authors would consider this paper a hoax, because they consider themselves objective scientists. But when they say, “We found that in the two years since Trump was elected in 2016, rates of low birth weight and preterm birth increased among black, Hispanic, and API mothers,” even though their own discontinuity graph shows an increase among whites in that time, I can’t help but say that this is a politicized version of the “story time” we often see in social science.

At this point, you might ask: What do I want the author and the journal to do? I would start with a plot of the raw data, without any discontinuities or absurd lines. Beyond that, present what you have, without storytelling and subset selection. If you want to write something with a political agenda, fine, but then separate it from the empirical argument. Such an article might not be published in Demography because it doesn’t reach the sweet spot of scientism + desired political conclusions… but it might not be okay not to publish there.

Why did you write this article?

Why did I bother writing all this? It’s not because this particular paper deserved all this attention. In fact, it seems to have received minimal press coverage. And I have nothing against the authors. I’m sure they’re just doing their best. Unfortunately, a lot of academic research in public health, public policy, and social sciences has this political undertone. What interests me more is how these kinds of papers, with weak science and sloppy political intentions, can end up in legitimate journals. I have some theories about this, which will be covered in future posts. But first, I had to wrap up this post and mention this particular study.

Also, I like the R example above. It’s a good reminder of how useful quick simulations can be.