In the summer of 2001, I kayaked solo for 66 days down the Nahanni, Liard, and Mackenzie rivers in Canada’s Northwest Territories. I saw little human presence on the rough Nahanni and muddy Liard rivers. But as soon as I reached the Mackenzie, part of the continent’s second-longest river system, I had to make way for a tugboat towing a massive barge loaded with gas, heating fuel, dried food, and other supplies heading for the roadless First Nations community downstream from Alberta, where the Mackenzie Highway ends in Wrigley. More than once on cold, foggy nights, I was woken from my tent by the ear-piercing blast of the tugboat’s horn.

These days, the horn sounds much less frequently, because the Mackenzie River, part of the continent’s second-longest river system as it flows northwest to the Arctic Ocean, is sometimes not deep enough to float the barges. In fact, the government-owned company that operates the towboats stopped service entirely this year when it became clear there wasn’t enough water in the river—even in late spring when the ice had melted. In June, the Canadian Coast Guard announced that services, including water response and navigational aids maintenance, were “impacted” along nearly 1,000 miles of the river.

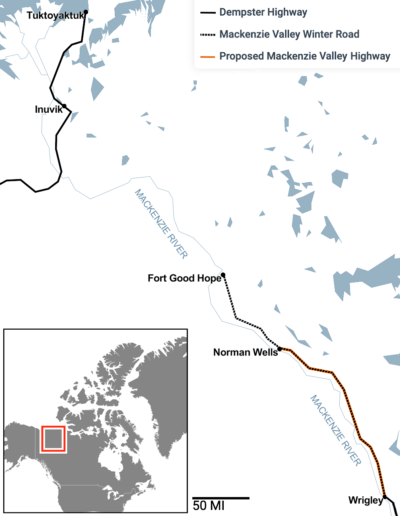

With fresh and dried food, essential building materials and fuel now being flown in and prices skyrocketing, residents of five communities in the Sahtu region are calling on the Canadian government to build a $1 billion road and bridge. Known as the Mackenzie Valley Highway project, the road and bridge will be a lifeline, connecting them to other communities and services in the south. Many residents are now rationing fuel and bringing in food from the south while they are on vacation or receiving health checks and treatment.

Water levels in the McKenzie River have never been this low, and all signs point to climate change making things much worse.

During low water periods, supplies were trucked thousands of miles north from the south along the Alaska and Dempster Highways, then barged in from the Arctic Ocean via the Mackenzie River. But given the water shortages for so long, this solution never materialized, and all signs point to climate change making things much worse.

“The biggest issue for the people who live here is what’s going to happen next year and the years after that as the climate continues to warm and the rivers dry up,” says Todd McCauley, who is leading a campaign for the road that his mother, a Dane First Nation chief, championed years ago.

“Just look at Mackenzie Bay, where the barges are moored. [from the Arctic Ocean] “There’s no water on the docks at Norman Wells. There’s just mud.”

“For a very long time the North has been seen as a source of resources – beaver, fur, timber, metals, oil and gas – all developed by Southern companies financed by Southern banks and created for the benefit of distant Southern markets,” says Charles McNeely, a Fort Good Hope resident and chairman of the Dene and Metis-run Sahtu Secretariat, which is responsible for implementing a range of services to five communities in the area.

“In return, North Korea lost our land and resources, and our families were scattered. [by the residential school program]Our culture and language have been discredited, our children have been abused. Wasn’t that a fair exchange? Why not try something different for a change?”

The Dempster Highway cuts through the desolate wilderness of northern Canada, with remote communities struggling to build another road to transport essential goods.

Brian Martin / Alamy Stock Photo

Increasingly warmer, drier weather, shrinking winter snow cover and rapidly melting ice sheets have reduced mid- to late-summer flow along most of the continent’s Arctic rivers for years. While boating down the Alaskan side of the Yukon River with retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Skip Ambrose last June, he said he had never seen river levels this low in his 50 years of surveying peregrine falcon nests there. Great Slave Lake, the fifth-largest lake in North America, which flows into the Mackenzie River, was at its lowest level on record.

But people living along the Yukon and Mackenzie rivers aren’t just stressed by low water levels. High water levels, the result of much earlier melt this year, are also causing disruption. In 2021, flooding along the Hay, Mackenzie, and Little Buffalo river systems caused $40 million in damage. In 2023, water levels along the Yukon River in Eagle, Alaska, rose, flooding streets and hotels.

University of Saskatchewan water expert John Pomeroy suggests northerners should prepare for more extreme rainfall events due to climate change, which is also accelerating the retreat of glaciers and accelerating the thawing of permafrost and snow-covered land earlier and at shorter intervals.

“What we are expecting is much higher and faster flows, higher flood peaks, and less water flow on hot summer days,” he said, warning of serious consequences for water management and navigation.

Conservationists worry that voting in favor of the road would strengthen the arguments of other interests lobbying for road construction in the Arctic.

Pomeroy’s observations have been echoed in other studies, including recent ones. calculated From 1984 to 2018, the flow of 486,493 rivers in the Arctic was studied. The scientists found significant changes in the speed and timing of river discharge during the spring snow and ice melt period and the summer intermittent streamflow period.

Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently combined field observations and numerical modeling to figure out how the 8.7 million square miles of the Arctic are likely to change over the next 80 years. They suggest that by 2100, the amount of runoff from underground channels into the Far North will increase by 25 percent, with increased precipitation but less water flowing in late spring and summer.

The Yukon Glacier, which slipped from the St. Elias Icefield, one of the largest in the world, has lost 22 percent of its surface area since 1958. The Brinnell-Bologna Icefield in the Ragged Mountains of the Northwest Territories, which feeds meltwater into the MacKenzie River system, is disappearing even faster.

Yale Environment 360

For years, Sahtu residents have been asking the Canadian government for a two-lane gravel road about 200 miles long. The road is estimated to cost at least $700 million, and the government allocated about $70 million in 2018 to study its feasibility. But in February of last year, Canada’s environment minister announced that the government would no longer invest in large-scale new road construction. The minister, Steven Guilbeault, said the money spent on asphalt and concrete “would be better spent on projects that help us combat climate change and adapt to its impacts.”

After public outcry, Northwest Territories Member of Parliament Michael McLeod was quick to say the MacKenzie Valley Highway project was still up for debate, as was Gilbo.

Still, conservationists worry that agreeing to road construction will strengthen the case of other communities and the mining industry that have been lobbying for road construction in other parts of the Arctic. For example, mining companies and Inuit in the Kitikmeot region of the central Arctic have been trying to build a road, albeit unsuccessfully, so far. port It is planned to be built along the Arctic coast, with a road linking Bathurst Bay to inland mines and mining exploration areas.

Earlier this year, Nunavut, a Canadian Inuit territory, hired an engineering firm to study the project’s potential. 450 mile road It will connect four areas west of Hudson Bay. A separate 200-mile route to Baker Lake, further inland, is also under consideration. Neither this road nor the McKenzie Valley Highway can be built without significant federal funding.

To understand why the federal government is reluctant to fund Arctic roads, it helps to understand the fate of other northern highways and how a rapidly warming Arctic could affect such infrastructure.

People in the Satu region have invested more in environmental protection and carbon capture than anywhere else in the South.

Opened to the public in 2017, the $300 million, 87-mile all-weather road from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories was meant to attract tourists to the Inuvialuit village of Tuktoyaktuk and lower the cost of energy development along the Arctic coast. But few tourists were willing to make the long, arduous drive, and oil and gas companies pulled out of the area before the road was even completed. Today, Tuktoyaktuk is slowly sliding into the ocean, threatened by rising sea levels, powerful storm surges, and rapidly thawing permafrost.

Maintaining the Arctic road has also been expensive. Just a few years after the Inuvik to Tuk highway was completed, the government spent an additional $13.5 million to build the road in areas where permafrost was melting. Climate-related maintenance costs for the Yukon highway network are $169,000 per yearConstant dollar basis from 1994 to 2021.

The Mackenzie Valley Highway won’t cause too many headaches, according to University of Alberta scientist Duane Froese, who has been conducting permafrost studies in the Sahtu area for the past several years.

“Inuvik has less permafrost and less ice-rich permafrost than the Took Highway,” he says. “Most of this route follows the Teal Plains, which are less likely to have significant ground ice in that area.”

Left: A liter of milk costs $12 at a grocery store in Port Good Hope. Right: Charles McNeely, president of Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated.

Satu Office Corporation

Conservation groups have been silent on the issue for several reasons. First, the Mackenzie Road right-of-way does not pass through a vital wildlife corridor like the Bathurst Inlet Road. Second, they do not want to jeopardize their relationship with the people of the Western Arctic. There is still a lot of wilderness there that needs to be protected, and the Dene need to be partners because they own and have rights to vast tracts of land.

The Satu have already invested more in conservation and carbon capture than any other jurisdiction in the South. They have agreed to allow for a new national park. Natsuihkoh — established on their territories. And organizations such as the Boreal Songbird Initiative and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society praised them Recently agree to protect Carbon-rich wetlands stretch across 4,000 square miles along the Ramparts River near Fort Good Hope.

The Satu hope the road will make it easier and cheaper to get necessities. But they also anticipate economic opportunities, with tourists, hikers, hikers and paddlers traveling to the new park and the region’s pristine mountains and tundra rivers.

Road advocates like McCauley point to another reason for building it: A road would make it easier to clean up the piles of scrap metal, broken-down vehicles, leaking batteries and other toxic materials from mining and other development activities that have accumulated in First Nations communities along the Mackenzie and Inuit communities on the Arctic Islands for decades.

“The first two roads,” the Dempster Highway and the Inuvik to Tuk road, “were built to take resources out of the north,” says McNeely of the Sahtu Secretariat. The next road, which McNeely will call the Trudeau Road if approved by the current prime minister, “will bring the world north.”