Authors: Hjalte Fejerskov Boas, PhD student in Economics, University of Copenhagen, Niels Johannesen, Professor of Economics and Business, University of Copenhagen, Claus Kreiner, Professor of Economics and Director of the Center for Economic Behavior and Inequality (CEBI), University of Copenhagen, and Lauge Larsen, PhD student, Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen. Student, Gabriel Zucman, Professor of Economics at the Paris School of Economics. Originally published on VoxEU.

While the financial secrecy of offshore tax havens has historically provided ample tax evasion opportunities for wealthy individuals, the automatic exchange of information between tax authorities is an ambitious attempt to enable tax enforcement. This column explains how information exchange can significantly improve tax compliance through repatriation of offshore assets, self-reporting of offshore financial income, and audit efforts targeting offshore tax evasion.

Over the past decade, more than 100 countries, including all major offshore financial centers, have adopted automatic exchange of banking information. They now systematically collect information about bank accounts owned by foreigners and automatically provide this information to the relevant foreign tax authorities. The exchange of information relates to an individual’s financial assets, either directly or indirectly through holding companies, trusts, etc.

The purpose of automatic information exchange is to curb foreign tax evasion, an important policy challenge in a globalized world. Private wealth in offshore tax havens amounts to trillions of dollars (e.g. Zucman, 2013), overwhelmingly belonging to the wealthiest individuals (e.g. Alstadsæter et al. 2018a, 2018b, 2019), who – at least until recently – largely avoided taxes. .

In a recent paper (Boas et al., 2024), we study the impact of automatic information exchange on tax compliance. Our lab is located in Denmark and has built a unique data infrastructure encompassing all 300,000 intelligence reports on foreign bank accounts received by Danish authorities, as well as micro-data on the income, wealth and cross-border bank transfers of approximately 5 million adults. matches . taxpayer.

repatriation

We first ask whether the Automatic Information Exchange has led taxpayers with offshore bank accounts to repatriate assets by leveraging transaction data on fund transfers from tax havens.

As Figure 1 shows, transfers originating from personal accounts in tax havens (‘repatriations’) have increased differentially since 2013 compared to other transfers originating in tax havens (‘other transfers’). This indicates that the G20 decision resulted in a strong repatriation reaction. Automatic information exchange to carry out new global standards and follow-up efforts to implement this decision.

Figure 1 repatriation

We also document that repatriation from tax havens is associated with a one-to-one increase in total wealth on tax returns and corresponding increases in taxable capital gains and tax liabilities. This means repatriation will occur from non-compliant accounts and tax compliance will increase.

Voluntary reporting

We then consider whether taxpayers who have not repatriated foreign assets will be more likely to self-report financial income from foreign accounts upon the commencement of the automatic exchange of information.

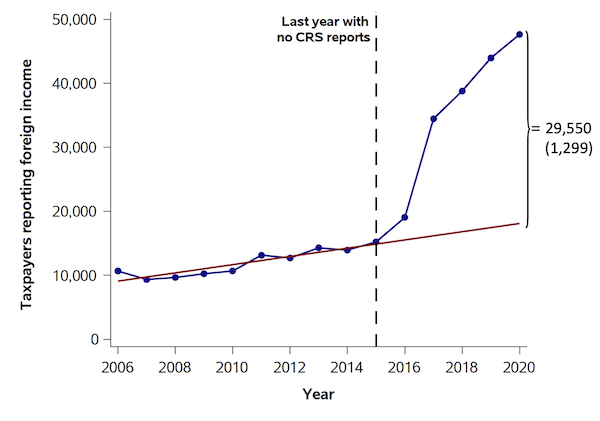

As shown in Figure 2, the number of taxpayers reporting foreign financial income directly on their tax returns increased dramatically with the launch of automatic information exchange in 2016-2017. In fact, the number of self-reporters has roughly tripled in a short period of time.

Figure 2 Voluntary reporting

\

We interpret the increase in voluntary reporting of foreign financial income as taxpayers responding to information exchange. We provide two types of evidence to support this interpretation.

- First, we consider separately groups of taxpayers who were treated at different points in time due to the staggered adoption of automatic information exchange between foreign counterparties. For each cohort, the rapid increase in self-reporting coincides with the first year of information exchange.

- Second, we document explicit self-reported responses to letters from the Danish tax authorities informing taxpayers that they have received information reports on foreign bank accounts.

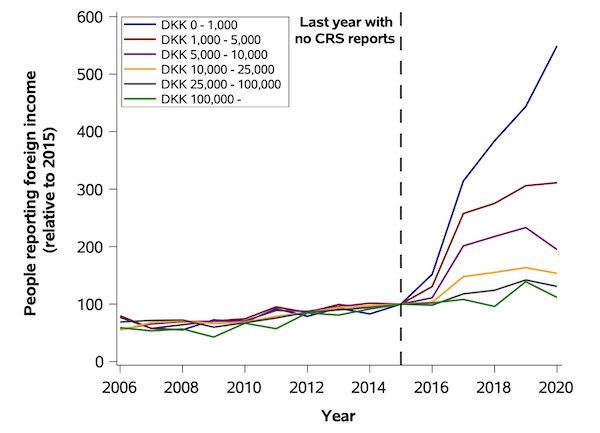

The results suggest that a large number of taxpayers have been compliant through self-reporting, but the impact on revenue appears to be minimal. This is <그림 3>As can be seen, this reflects that the increase in voluntary reporting is being led by taxpayers with low levels of overseas financial income.

Figure 3 Voluntary reporting by overseas income range

]

improved audit

Finally, we study the extent to which audits of overseas financial income can more effectively detect overseas tax evasion and utilize new information on overseas accounts.

We worked with the Danish tax authorities to design an audit effort targeting a random subset of taxpayers for whom a comparison of their tax returns and foreign intelligence reports revealed significant tax evasion. Specifically, we select 500 taxpayers for audit among all taxpayers whose interest and dividend income declared by foreign banks exceeds the foreign interest and dividend income declared by the taxpayer in his/her tax return by more than 5,000 Danish kroner.

The audit results allow us to estimate the offshore tax evasion that tax authorities could potentially detect through this type of audit effort due to new information reporting by foreign banks. Our results show significant audit potential, but on a smaller scale than other impacts, potentially reflecting that a large amount is already compliant through repatriation and self-reporting.

argument

Combining estimates from different empirical designs, we conclude that automatic information exchange has closed approximately two-thirds of Denmark’s offshore tax gap. Repatriation appears to be the biggest contributor to increased tax compliance, but improved self-reporting and audits also play a role that cannot be ignored.

This suggests that automatic information exchange is a relatively successful approach to tackling offshore tax evasion. This is especially true when compared to previous policy approaches that have largely failed (Oldenski et al. 2011, Johannesen 2014, Johannesen and Zucman 2014, Johannesen et al. 2020). However, compared to domestic third-party reporting, cross-border information exchange still leaves significant room for non-compliance (Kleven et al. 2011). Our paper discusses various possible explanations.

It is important to emphasize that our findings do not necessarily extend to other countries. In particular, developing countries that lack the capacity to process information reporting from foreign banks may benefit less from automatic information exchange (Johannesen 2024).