Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Christopher A. Hartwell (ZHAW School of Business and Law, Switzerland) and Pierre Siklos (Professor Emeritus at Wilfrid Laurier University and Balsillie School of International Affairs, Canada).

The paper we wrote together is scheduled to be published in: Central Bank International JournalWe argue that underperforming central banks, especially those that consistently miss their inflation targets, not only undermine their own credibility but also undermine the institutional quality of the country. So if we ask, what damage can underperforming central banks do? The answer is actually quite a lot. This conclusion has far-reaching implications for institutional development, weakening overall economic resilience.

Since the spread of central bank autonomy policies around the world, monetary authorities have played, some would say, an overly large role in determining the course of national economies. Given this importance, we assume that the performance of central banks can have a significant impact not only on economic performance but also on the strength of institutions. For example, a short-term decline in central bank confidence, a flow variable, can have a significant impact on overall trust We place our trust in variables such as slow-moving stocks and place them in central banks. If trust in central banks begins to wane, there is the potential for a more widespread decline in the quality of state institutions. Weak institutions weaken the institutional resilience of the economy. We think of resilience as the ability of a country to potentially withstand the shocks of economic and political diversity.

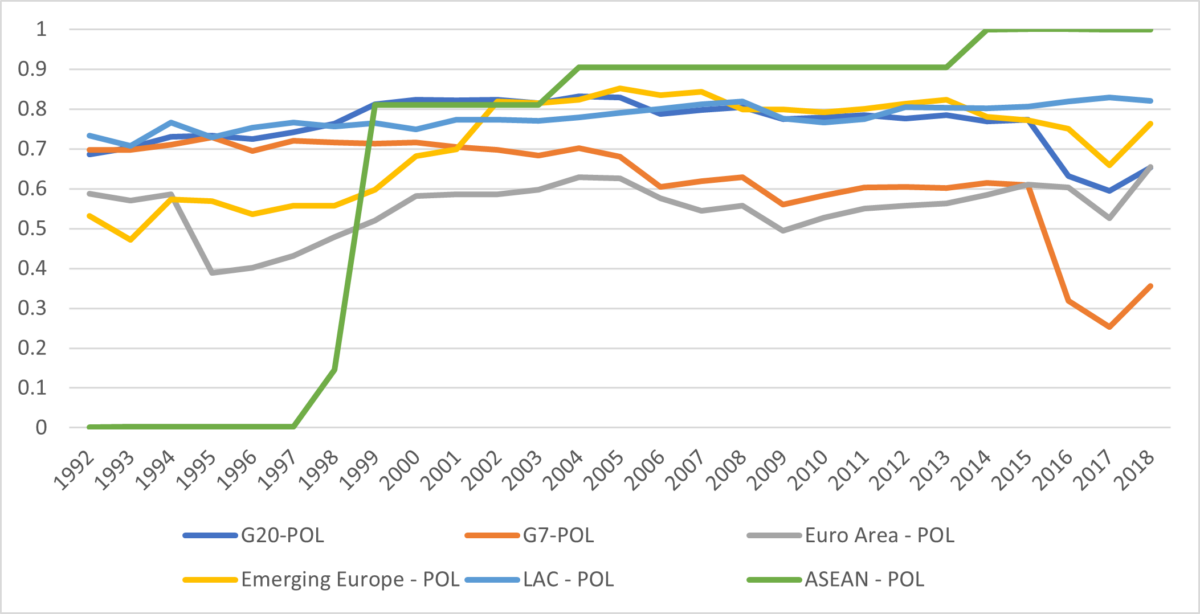

To quantify this relationship, we use a combination of economic factors (e.g., the extent of property rights, the extent of trade and financial openness, and exchange rate flexibility) and political factors (e.g., democracy, administrative constraints, and the size of government finances). This index captures properties that should be positively correlated with resilience, except for government size, which is negatively correlated (large governments have little room to maneuver in the face of shocks). The graph below shows the results of an examination of economic and political resilience (indices ranging from 0 to 1) for a selected group of countries. However, we generated these indices for each of the 90+ individual countries in our dataset (representing over 80% of the world’s population and GDP). Although our data go back to the 1960s, it was not until the 1990s that the most extensive array of variables considered became consistently available for countries outside the advanced economies. As shown below, there was considerable variation over time in the 1990s and 2000s, and the gaps between the indicated group of countries showed little sign of convergence by the end of the sample compared to the early 1990s, but central bank resilience increased globally. The gap in political resilience remains across the sample considered, and has narrowed markedly for the G7 since 2015, before the pandemic and recent events. The G7 was among the most politically resilient countries in the early 1990s.

Figure 1: Economic resilience. Higher scores indicate greater resilience.

Figure 2: Political resilience. A higher score indicates greater resilience.

We compare this index to a measure of central bank efficiency, which consists of three separate linear components. First, we compare the central bank’s inflation performance to its stated target in the case of inflation targeting, or to its implicit target (a five-year moving average of inflation outcomes) in the case where the bank has no stated target. Second, we create a measure of monetary policy uncertainty, which compares the difference between inflation and output outcomes to forecasts. Finally, we measure how much the country’s inflation performance diverges from the rest of the world.

Using generalized method of moments (GMM), model selection techniques, and local forecasting estimates of VAR, we find that a 1% decline in central bank confidence corresponds to an average 3.6% decline in a country’s institutional resilience since the 1990s. In short, the more a central bank loses confidence, either by missing its inflation target or by diverging from the global trend, the more it harms a country’s overall institutional resilience.

The results of this study once again highlight that although central bank autonomy can lead to better inflation outcomes, even when independence is controlled, central banks can still pursue poor policies or be inefficient. Central banks that perform better – that is, those that focus primarily on price stability – are better for the economy. More importantly, because central banks play an important institutional role in the economy, a country’s overall institutional quality may also depend on how well its central bank performs. Although our results are based on incomplete indicators, we attempted to establish the sensitivity of our results to definition changes, sample period changes, and data sources within the constraints of data availability. Our main results remain fairly robust across the estimation techniques used.

This post was written by: Christopher Hartwell and Pierre Cyclos.