Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution. Luisa Carpinelli, Filippo Natoli, kevin palala, Luca Rossi, Sergio Santoro and Massimiliano Spregola; Bank of Italy, DG – Department of Economics, Statistics and Research, Developed Economies and Macroeconomic Policy. The views expressed in this column represent those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy or the ESCB.

| This analysis critically evaluates the forecasting performance of Federal Funds Futures (FFF) and the Federal Reserve’s Summary of Economic Outlook (SEP) in the context of forecasting the federal funds rate. Although FFF is a widely used market-based measure, its reliability has been questioned due to frequent forecast inaccuracies. In early 2024, these concerns were reignited by significant differences between FFF and SEP forecasts. FFF estimates reflect both market expectations and risk premiums, which can distort forecasts, especially for long-term forecasts. By using the Survey of Primary Dealers (SPD) and looking at a simple model-free measure of risk premium, this analysis suggests that FFF can guide forecasts for this year, but that the SPD median forecast should be preferred for longer time horizons. A visual comparison via a “spaghetti chart” indicates that both the Fed and the market often miss the mark when it comes to predicting future policy rates. The relative average absolute forecast error shows that the Fed’s forecast error is, on average, only slightly better than the market’s forecast error. However, certain episodes, such as after the SVB collapse in Q2 2019 and Q1 2023, show that market misjudgment was primarily influenced by risk premiums. This analysis provides a robust comparison of the forecasting capabilities of the Fed and the markets, highlighting the need to complement FFF and SPD forecasts to better understand the differences. |

Because U.S. monetary policy is a key macroeconomic driver both domestically and in other countries, expectations about the path of the federal funds rate are monitored and analyzed globally.[1] Financial markets are an important source of expectations for federal funds due to their high frequency of availability. By far the most commonly used indicator is the quote for 30-day federal funds futures (FFF) traded on the Chicago Board of Trade. These futures are settled based on the monthly average of the daily effective federal funds rate, providing a natural market-based measure of what investors believe the Fed will decide in the coming month. The downside to this indicator is that its out-of-sample predictive performance is questionable because it often fails to accurately predict what the Fed will do.[2]

Doubts about the reliability of the FFF resurfaced in early 2024 with very large differences between the mid-term policy rate forecasts reported by the Fed in its Summary of Economic Outlook (SEP).[3] Here comes the FFF quote. As of mid-January, FFF suggested the Fed would cut interest rates by about 150 basis points, which is double what the Fed reported in its December SEP a few weeks ago (see Figure 1).

Sources: Refinitiv, Federal Reserve Bank, Chicago Board of Trade. The solid blue line represents the FFF price in December 2024. The settlement of these futures is based on the average daily effective federal funds rate (data published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York) applied throughout the month. The blue dotted line is the FOMC members’ central federal funds midpoint target range appropriate rate projection for the end of 2024, obtained from the Quarterly FOMC Summary of Economic Outlook. The black dotted line is the midpoint of actual federal funding in the target range.

Critics of the market outlook certainly have a point. FFF has missed many times what the Fed would have done by a wide margin. But before you throw out your market predictions, you should look deeper into some related issues. Can we take for granted that FFF is always a valid proxy for market expectations? Has the Federal Reserve done a good job of predicting the future direction of policy rates? More broadly, can markets or interest rate makers be better at predicting policy rates?

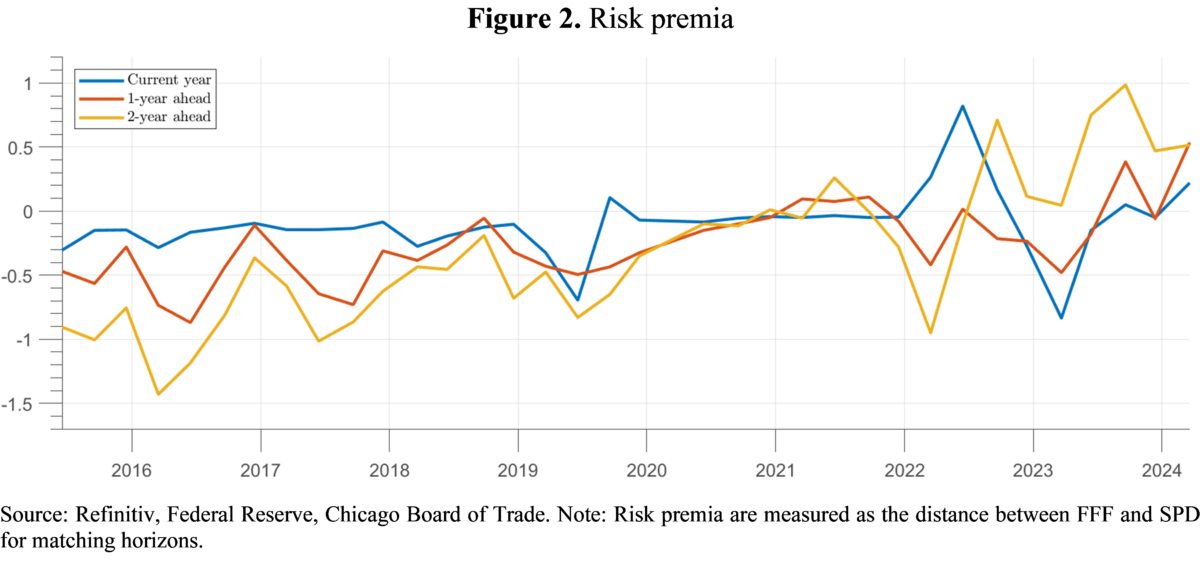

Before we get into the actual horse racing, let’s address the first of the questions above. In other words, can FFF always be interpreted as market expectations about the federal funds rate? The basis for this question comes from the fact that FFF estimates, like many other derivatives, can be viewed as the sum of expectations about the underlying variables of interest and the risk premium required by risk-averse investors. To assess the possible relevance of the second component, we quantify it in a very simple way by utilizing the Survey of Primary Dealers (SPD) maintained by the New York Federal Reserve. The survey is conducted before each FOMC meeting and, like the SEP, collects forecasts for year-end policy rates, GDP growth, unemployment and inflation, among other things, making it a natural choice to compare the market’s and the Fed’s views. Around the FOMC meeting.[4] We then obtain a model-free measure of this year’s risk premium by taking the simple difference between the FFF estimate on the last day for which primary dealers can write SPDs and the median expectations reported by primary dealers to the Fed in their SPDs. One-year and two-year forecasts (see Figure 2).

Risk premiums are relatively low for current year forecasts (with some exceptions) but tend to be significant for forecasts one and two years ahead. This means that FFF can provide biased and misleading estimates of market expectations for the horizons included in many of the spaghetti charts above. Therefore, our suggested rule of thumb is to rely on the more timely FFF for current year forecasts, supplementing the FFF with the SPD median forecast and instead looking at the SPD for a longer horizon. As we will see later, this year’s FFF movements may be dominated by risk premiums, especially during turbulent times.

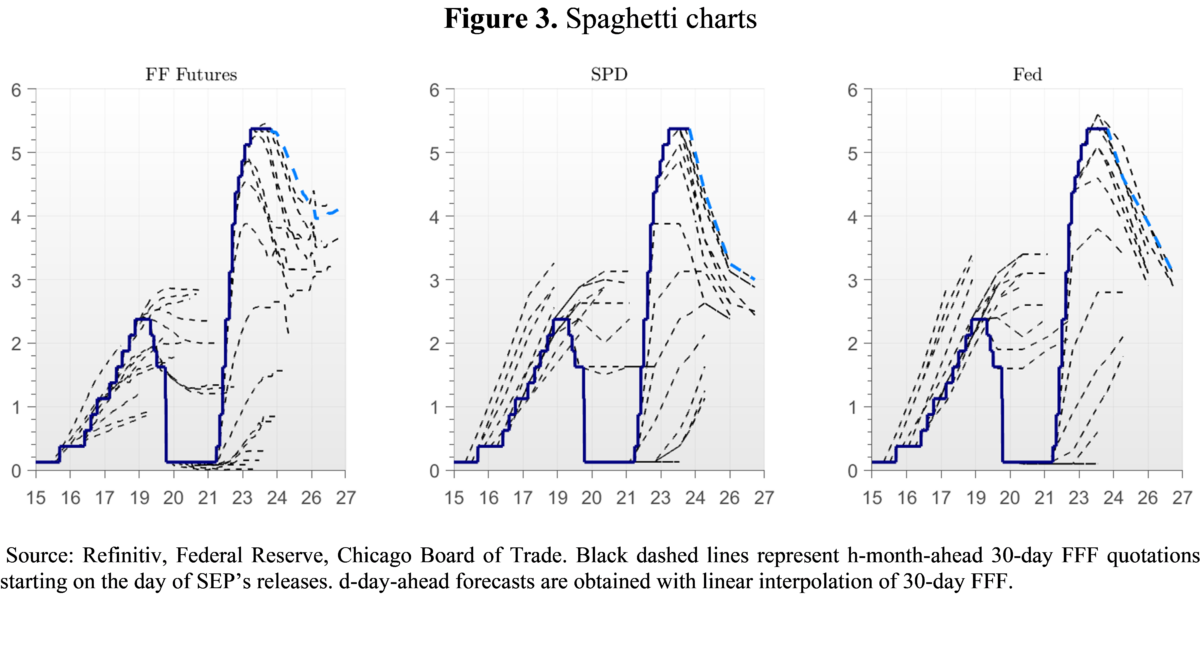

Regarding the first question about the validity of FFF as a proxy for market expectations, we suggest the popular “spaghetti chart” reported in the analysis above, also for FOMC interim forecasts (see Figure 3). From a quick visual inspection, it is clear that the Fed is often looking ahead to future decisions, and the results are somewhat unsatisfactory. However, spaghetti charts are only a very qualitative first step in measuring the Fed’s relative performance relative to the market. A more analytical approach is needed.

Let us now focus on the formal comparison between the average forecast accuracy of the market and SEP. As an indicator, we look at the relative average absolute forecast error (MAFE), calculated as the Fed’s average MAFE minus the market’s average MAFE. We find that the Fed’s forecast errors are, on average, only at most 3 basis points lower than the market’s forecast errors. So the Fed doesn’t consistently outperform the market. on averageThis means that FOMC forecasts are unconditionally identical to market forecasts.

Nevertheless, differences appear in several episodes, even if on average there is no significant systematic discrepancy. First, in the second quarter of 2019, year-end FFF estimates were lowered from 2.3% to 1.7%, pricing in a 60bp rate cut. Debate in 2019 centered around concerns about when one of the largest expansions in U.S. history would end and whether it would pose significant global risks that could put the brakes on the U.S. business cycle. At that time, inflation was also quite low. Despite market expectations, the FOMC maintained its forecast at 2.4% at its June meeting. But this year the Fed actually decided to lower interest rates to 1.6%. At first glance, this appears to be an example of the market getting a better look at the trajectory of the federal funds rate.

Conversely, after the bankruptcy of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in March 2023, FFF fell from 5.6% on March 8 to 4.0% in three trading days, but at the March FOMC meeting, the Federal Reserve maintained its forecast for the end of 2023 at 5.1%. . For the remainder of the year, the Fed has raised interest rates by one point to 5.4%. Judging by FFF alone, this turned out to be a colossal failure of market valuation.

nevertheless, both the 2019-Q2 and 2023-Q1 SPD forecasts were very similar to the FOMC’s forecasts, thus suggesting that in both specific cases these differences were primarily due to risk premiums. However, many analysts believe that the decline in FFF equates to a decline in market expectations about the policy rate.[5] Therefore, the above example shows that during turbulent times, even over relatively short periods of time (less than a year), FFF can be an unreliable measure of market expectations, and analysts should use SPD instead. In general, we think it’s wise to compare FFF to pure expectations (undistorted by risk premiums) whenever possible to get a rough idea of whether you can trust FFF in the first place at any given moment.

Our work also exploits information about additional macro variables available in SEPs and SPDs to reveal the underlying reasons why the Fed and markets may diverge. For example, in 2022, the market has repeatedly predicted that cumulative tightening by the end of 2023 will be milder than the Fed had intended to deliver. We find that this is at least due to i) the market expecting lower inflation and weaker GDP growth, and ii) the market expecting slightly lower inflation. R*. Moreover, we find that larger differences between the Fed and the markets can be attributed to periods of relatively high uncertainty, as judged by the central tendency available in SEP, the interquartile range in SPD, or Treasury volatility implied by MOVE. .

In conclusion, we are able to comprehensively and consistently compare the views and forecast performance of the Fed and the markets, and can use our framework to assess additional differences going forward. We present evidence that FFF alone can be a seriously biased measure of market expectations because of the presence of significant risk premiums over longer or turbulent periods. We then propose to complement FFF with SPD predictions. On average, we find that the Fed is no better than the market at predicting its own decisions. However, distinct differences emerged in certain situations. This can be explained, at least in part, by exploiting the additional predictions available in both SEP and SPD.

[1] See, for example, Miranda-Agrippino, Silvia, and Hélène Rey (2020).US monetary policy and global finance to give,” 『Economic Studies』, 87(6), 2754–2776, Degasperi, Riccardo, Hong Seok-gi, Giovanni Ricco (2020) “Global Transmission of U.S. Monetary Policy.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14533.

[2] for example “Investors May Be Misunderstanding the Fed Again“, The Economist, January 24, 2024; “Investors are almost always wrong about the Federal Reserve”, Wall Street Journal, February 8, 2024.

[3] SEP is quantitative information collected quarterly on the inflation, growth, and unemployment projections of individual board members and each Federal Reserve president. This includes expectations about future federal funds rates relative to the macroeconomic outlook. Surveyed members are also asked which path they believe is appropriate for the federal funds rate, given their economic forecasts.

[4] Disadvantages of SPD are that i) it can only be held 8 times a year, i.e. the same frequency as FOMC meetings; ii) Announced three weeks after the FOMC meeting. iii) Because the survey is compiled approximately 10 days before each FOMC meeting, the information set of primary dealers is less complete than that of FOMC members because important macroeconomic data may be released during that period. But a very important benefit is that it provides clean market expectations for the federal funds rate. A caveat to this inference is that we implicitly assume that the expectations of the primary dealer will be consistent with the expectations of agents investing in FFF. Comparing SPD expectations with expectations from the Survey of Market Participants (SMP) maintained by the New York Federal Reserve, we find that the two are very similar, supporting our assumption.

[5] for example “SVB collapse causes U.S. banking stocks to plummet, Treasury bonds to rally“, Financial Times, 13Day March 2023.

This post was written by Luisa Carpinelli, Filippo Natoli, Kevin Pallara, Luca Rossi, Sergio Santoro and Massimiliano Sfregola.