Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution. Jamel Sadaoui (University of Paris 8).

Recent literature has established that climate risk reduces fiscal space (see, e.g., Beirne et al. (2021)). The rationale is intuitive and easy to understand: financial markets will price the impact of climate risk in the form of higher bond yields and lower ratings on long-term foreign currency debt. This Climate Risk Premium It will have a significant negative impact on the financing of the green transition, especially in emerging markets. However, the literature has not explored the role of financial development and political stability on climate risk premiums. Intuitively, it seems reasonable to think that: Countries with better financial systems and more stable political environments will face less pressure on their fiscal capacity. Recently Papers by John Beirne, Dong-Hyeon Park, Jamel Saadaoui, and Gazi Salah UddinWe investigate this issue. For a sample of 199 economies from 1990 to 2022, we first empirically confirm that climate risk has a negative impact on fiscal space. We find that the impact is most pronounced in economies most vulnerable to climate change. However, our evidence suggests that political stability and financial development can mitigate the impact. We also identify nonlinearities in the climate risk-fiscal space linkage. More specifically, the impact of climate risk on fiscal space is larger when fiscal space is most constrained, i.e., in the upper quantiles of the distribution.

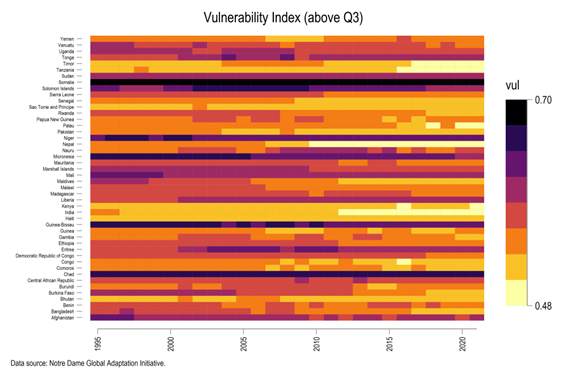

Figure 1. Here is a heat plot for low vulnerability scores.

To measure climate risk we use: ND-GAIN Vulnerability Score. This score is a forward-looking composite measure of vulnerability to climate change. In Figures 1 and 2, we see that countries located in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are the most vulnerable to climate hazards. In addition to the presence of more developed countries in Figure 1, we find several countries that do not belong to the more developed group of economies in terms of economic development. These countries have lower vulnerability scores (i.e., higher resilience to climate hazards) because they score well in some subcategories of the ND-GAIN overall vulnerability score, such as the infrastructure quality or energy autonomy subcategories.

Figure 2. Here is a heat plot for high vulnerability scores.

In Figure 2, we can observe countries with higher vulnerability (3rd quartile and above). These are countries that tend to be at lower levels of economic and institutional development. These countries also tend to have less developed domestic financial markets. Compared to the group of countries presented in Figure 1, this group of countries is more homogeneous. We find countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. These countries still lack paved road coverage, access to electricity, and access to reliable drinking water. For example, Chad and Afghanistan have very high vulnerability scores for both agricultural capacity and health care coverage.

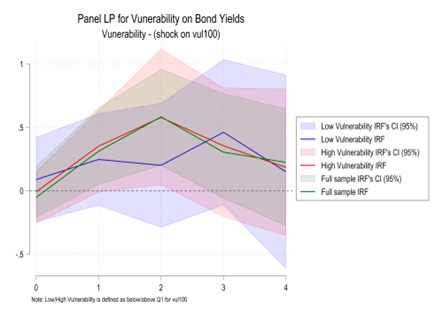

In Figure 3, we use panel local estimates and a list of domestic and global controls from the literature. Our baseline case for all countries shows that climate risk vulnerability leads to a statistically significant premium on sovereign bond yields, reflecting the excess return required by investors holding such debt. We also split the sample into low and high climate risk vulnerability groups based on the value of the vulnerability score. For countries that are less climate vulnerable, we find no statistically significant effect. This is consistent with economic intuition: low levels of climate exposure do not lead to a climate-related premium for sovereign bonds. For countries that are highly exposed to climate change, the effect on bond yields is significant, as expected. Interestingly, the effect is broadly consistent with the effect across the panel, suggesting that countries that are highly vulnerable to climate change may be driving the overall results.

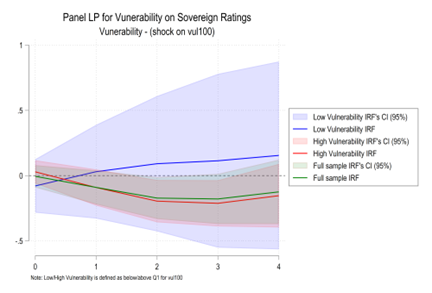

In Figure 4, we perform the same baseline analysis for our second measure of fiscal capacity, sovereign ratings. We find results consistent with those we did for bond yields, where climate vulnerability shocks lead to persistent declines in sovereign ratings for the full sample and for countries with high climate vulnerability. For countries with low vulnerability, we do not observe such persistent deterioration in sovereign ratings, as expected.

Figure 3. Panel LP on the impact of vulnerability to bond yields.

Figure 4. Panel LP on the impact of vulnerability on country ratings.

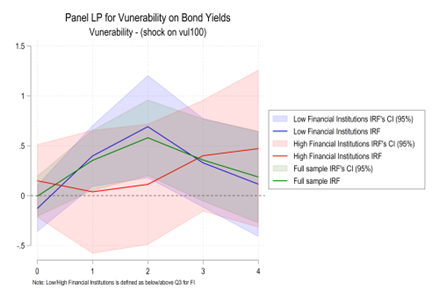

In Figure 5, we use the Financial Institutions Development Index (Svirydzenka, 2016) to examine the impact of financial institution development on the impact of vulnerability shocks on fiscal space. For countries with mature financial institutions, climate vulnerability shocks do not lead to an increase in bond yields.

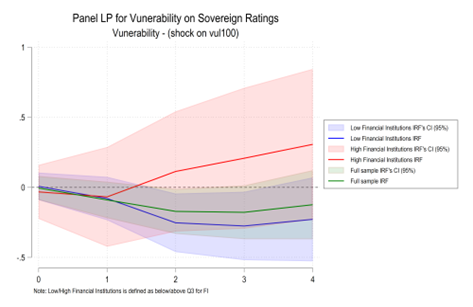

In Figure 6, we find that climate vulnerability shocks do not significantly affect sovereign ratings in countries with high levels of financial institutional development. On the other hand, climate vulnerability shocks consistently worsen sovereign ratings in countries with low levels of financial institutional development and in the overall sample, supporting the importance of sound financial institutions. The moderating effect of improved financial development on climate-financial linkages is intuitive, with greater depth and liquidity in regional financial markets and better developed insurance markets.

Figure 5. Panel LP (Financial Institutions) on the Impact of Vulnerability to Bond Yields

Figure 6. Panel LP (Financial Institutions) on the Impact of Vulnerabilities on Country Ratings

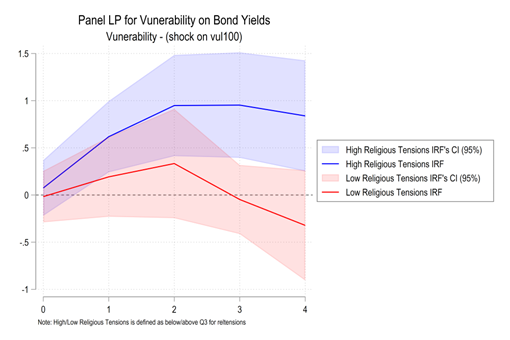

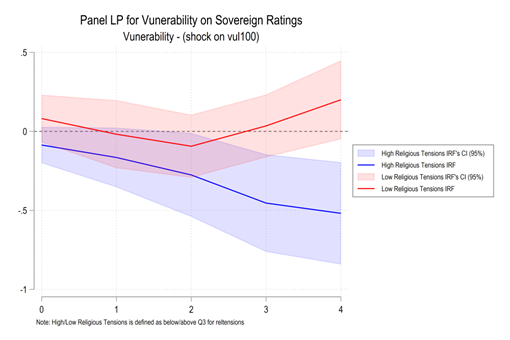

Our results are as follows: ICRG data (PRS Group) confirmed our main intuitions about the various aspects of political stability: external conflict, internal conflict, government stability, and ethnic tensions. Countries with more stable political systems had lower climate risk premiums. It is noteworthy that the climate risk premium is persistent only for one dimension of political stability, namely religious tension. This result may help policymakers understand the role of political stability and financial development in financing the ecological transition.

Figure 7. Panel LP (Religious Tension) on the Impact of Vulnerability to Bond Yields

Figure 8. Panel LP (Religious Tension) on the Impact of Vulnerability on National Debt Ratios

This post was written by: Jamel Sadaoui.