JW Mason By focusing on real exchange rates, I argue that relative prices are the main determinant of flows.

One of the major differences between orthodox Keynesian and (post)Keynesian approaches to international economics is this: Are trade flows primarily driven by relative prices or by demand?

Rather, I think income is very important. This is evidenced in my study of trade flows described here. Updated until 2024, it is estimated to be from 1980 to 2024.

Δ Express tea =β 0 + Φ Express t-1 +β 1 why *t-1 +β 2 cue t-1 + γ 1 Δy *tea + γ 2 Δq tea + you tea

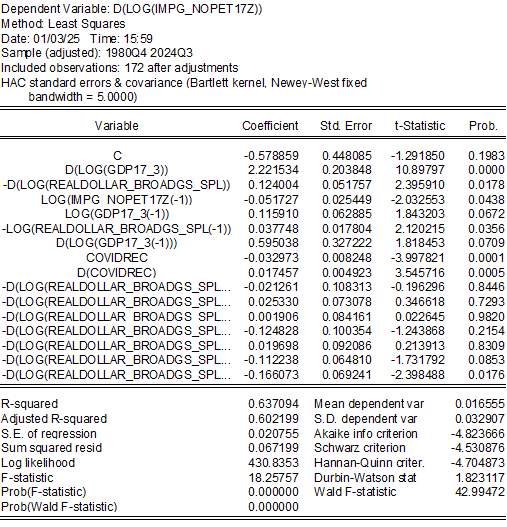

Δ Imp tea =β 0 + Φ Imp t-1 +β 1 why t-1 +β 2 cue t-1 + γ 1 Δy tea + γ 2 Δq tea + 7 lags in Δq tea + you tea

Each error correction model specification includes the covid dummy (2020Q1-Q2) and its first difference.

For U.S. exports of goods and services:

This means that the long-run elasticity of exports to the dollar exchange rate is 2.07, while the long-run elasticity of income (world trade-weighted GDP) is 1.47.

This compares to 2.3 and 1.9. Chin (2004).

For goods imports, the real exchange rate is also important, but it is more difficult to obtain statistically significant estimates.

The long lag in exchange rates is consistent with numerous studies showing that the effects of exchange rates take a long time to take effect (consistent with the graph in this post).

The long-run elasticity of goods imports (excluding oil) with respect to the dollar is 0.74, and the elasticity of US income with respect to the dollar is 2.24.

in Chin (2004)I got long-term estimates for total earnings of -0.2 and 2.3, respectively. in Chin (2010)For data up to 2010, we obtain estimates of -0.5 and 2.2, respectively, for imports of products other than oil.

Income is therefore important, as is relative price. I consider this to be the traditional view (e.g. Rose and Yellen, JME 1989), rather than the orthodox versus post-Keynesian view.

Now, for relative importance, we can look at the standardized (or “beta”) coefficient, which is the OLS coefficient divided by the standard deviation and multiplied by it. For export regressions estimated in first differences, the income “beta” coefficient is approximately four times the size of the exchange rate coefficient. For the first-difference equation for non-oil goods imports, the income “beta” coefficient is approximately 10 times the exchange rate coefficient.