As Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump campaigns for a second term in the White House, the former president has repeatedly promised to enact the largest deportation of undocumented immigrants in U.S. history. It’s a bold threat that legal experts say should be taken seriously, despite the significant technical and logistical challenges posed by deporting 11 million people from the U.S.

Even if only somewhat successful, Trump’s hard-line approach to immigration — with its laser focus on removing immigrants who live in the U.S. without permanent legal status — has the potential to uproot countless communities and families by conducting sweeping raids and placing people in detention centers.

Mass deportation would also, according to economists, labor groups, and immigration advocates, threaten the economy and disrupt the U.S. food supply chain, which is reliant on many forms of migrant labor.

The ramifications of a mass deportation operation would be “huge” given “immigrant participation in our labor force,” said Amy Liebman, chief program officer of workers, environment, and climate at the Migrant Clinicians Network, a nonprofit that advocates for health justice. Immigration is one of the reasons behind growth in the labor force, said Liebman. “And then you look at food, and farms.”

The possibility of deportation-related disruption comes at a time when the U.S. food system is already being battered by climate change. Extreme weather and climate disasters are disrupting supply chains, while longer-term warming trends are affecting agricultural productivity. Although inflation is currently cooling, higher food costs remain an issue for consumers across the country — and economists have found that even a forecast of extreme weather can cause grocery store prices to rise.

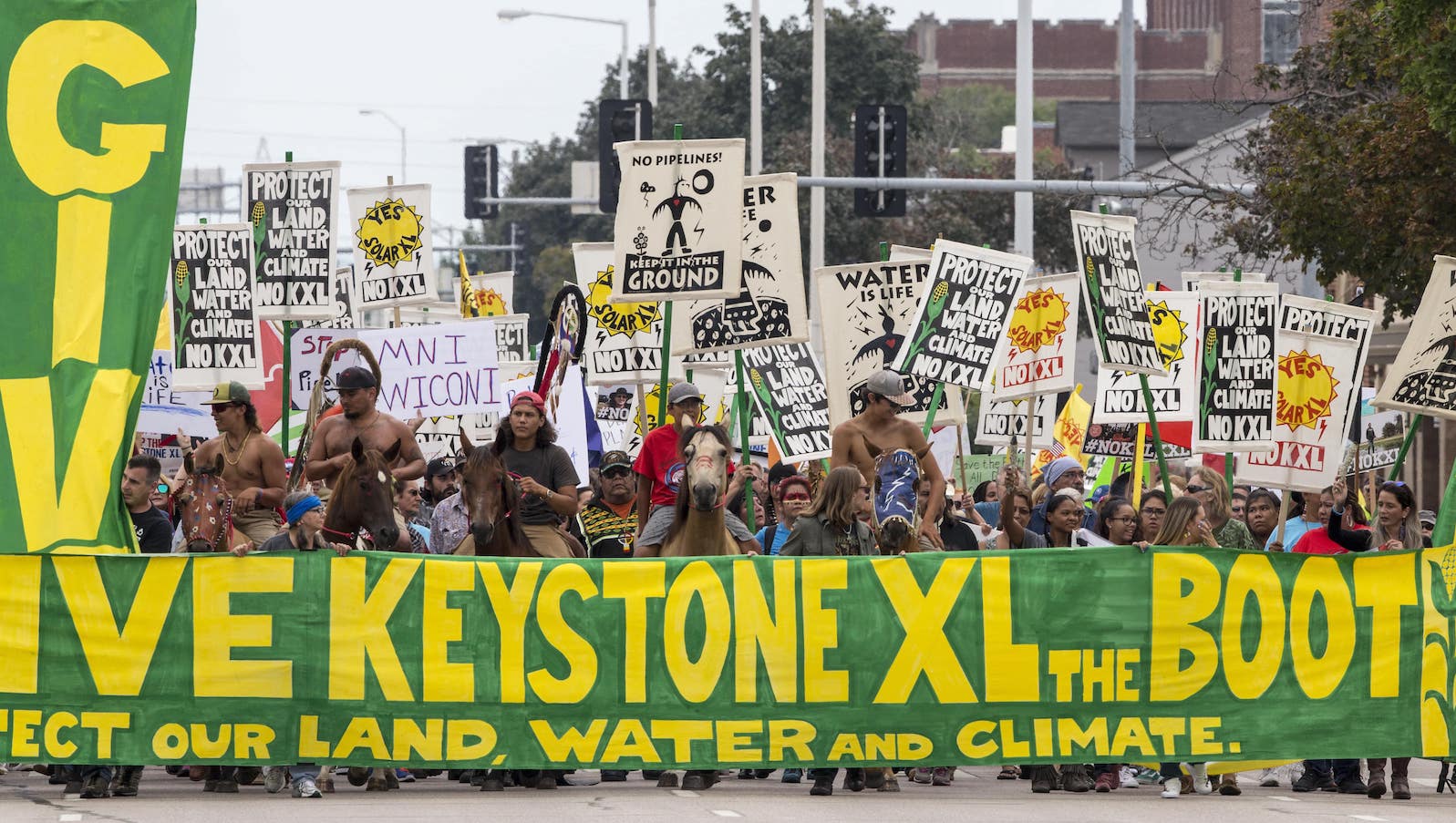

Mass deportation could create more chaos, because the role of immigrants in the American food system is difficult to overstate. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people, the vast majority of them coming from Mexico, legally obtain H-2A visas that allow them to enter the U.S. as seasonal agricultural workers and then return home when the harvest is done. But people living in the U.S. without legal status also play a crucial role in the nation’s economy: During the pandemic, it was estimated that 5 million essential workers were undocumented. And the Center for American Progress found that nearly 1.7 million undocumented workers labor in some part of the U.S. food supply chain.

Brent Stirton / Getty Images

A stunning half of those immigrants work in restaurants, where during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, they labored in enclosed, often cramped environments at a time when poor ventilation could be deadly. Hundreds of thousands also work in farming and agriculture — where they might work in the field or sorting produce — as well as food production, in jobs like machine operation and butchery.

The agricultural sector is just one of several industries in recent years that has experienced a labor shortage, which the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has classified a “crisis.” This ongoing shortage makes the Trump campaign’s proposal to force a mass exodus of people without legal status an inherently bad policy, said Liebman. “Part of me is like, ‘Oh, button your seatbelts, people, because who’s washing dishes in the restaurant, who’s freaking processing that chicken?’ Like, hello?”

The health and safety risks undocumented immigrants have undertaken to keep Americans fed — both in times of crises and during all other times — have been met with few legal and workplace protections. A bill to give undocumented essential workers a legal pathway to citizenship, introduced by Senator Alex Padilla, a Democrat from California, died in committee in 2023. Padilla told Grist he will continue working to “expand protections for these essential workers, including fighting for a legal pathway to citizenship.”

“Agricultural workers endure long hours of physically demanding work, showing up through extreme weather and even a global pandemic to keep our country fed,” he added. “They deserve to live with dignity.”

If this workforce were to be unceremoniously deported, without regard for their economic contributions to U.S. society or consideration of whether they actually pose a threat to their communities, it would be disastrous, according to Padilla.

“Donald Trump’s plans to carry out mass deportations as a part of Project 2025 are not only cruel but would also decimate our nation’s food supply and economy,” said Padilla, referring to the Heritage Foundation’s roadmap for a Trump presidency. (The Trump campaign did not respond to a request for comment.)

Farmers, who in the U.S. rely on many forms of migrant labor (including undocumented workers and H-2A temporary visa holders), have said that a crackdown on undocumented immigrants would essentially bring business to a grinding halt. In response to federal and state proposals to require employers to verify the legal status of their workers, the American Farm Bureau Federation has said, “Enforcement-only immigration reform would cripple agricultural production in America.” The Farm Bureau, an advocacy group for farmers, declined to comment on Trump’s mass deportation proposal, but a questionnaire the group gave to both presidential candidates states, “Farm work is challenging, often seasonal and transitory, and with fewer and fewer Americans growing up on the farm, it’s increasingly difficult to find American workers attracted to these kinds of jobs.”

Small farmers agree. A first-generation Mexican-American immigrant who works in Illinois as an urban farmer, David Toledo says that the consequences of mass deportation for the country’s food system would be hard to imagine, especially since he believes that “many Americans don’t want to take the jobs” that many undocumented workers currently fill for very low pay.

“We need people who want to work in fields and in farmlands. [Farmworkers] are waking up way before the sun because of rising temperatures, and living in horrible conditions,” said Toledo. He added that the U.S. should remember “that we are a welcoming community and society. We have to be, because we are going to see a lot more people shifting [here] from countries all over the world because of climate change.”

Getty Images North America

Stephen Miller, the advisor who shaped Trump’s hard-line immigration policy, has touted mass deportations as a labor market intervention that will boost wages for American-born workers. But analysts point out that previous programs aimed at restricting the flow of immigrant workers have failed to raise wages for native-born citizens. For example, when the U.S. in 1965 ended the Bracero Program, which allowed half a million Mexican-American seasonal workers to labor in the U.S., wages for domestic farmworkers did not increase, according to analysis from the Centre for Economic Policy Research. Additionally, a recent analysis found that a Bush- and Obama-era deportation program known as Secure Communities — which removed nearly half a million undocumented immigrants from the U.S. — resulted in both fewer jobs and lower wages from domestic workers. One reason is that when undocumented immigrants were deported, many middle managers who worked with them also lost their jobs.

Such a shock to the agricultural labor force could result in higher food prices, too. If farmers lose a large portion of their workforce due to mass deportation, they may not have enough people to harvest, grade, and sort crops before they spoil. That sort of reduction in the supply of food could drive up prices at the grocery store.

Many experts note that even attempting to deport millions of immigrants would disrupt the nation’s economy as a whole. “It will not benefit our economy to lose millions of workers,” said Debu Gandhi, senior director of immigration policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank. “There is no economic rationale for it.”

For instance, mass deportation would deprive governments of essential tax revenue. A report from the American Immigration Council found that a majority of undocumented immigrants — or three-fourths — participated in the workforce in 2022. This tracks with other analysts’ understandings of the undocumented workforce. “Undocumented immigrants, when they get to the United States of America, they have an intention to work, to make money and contribute not only to their families, but also to the federal, state, and local government,” said Marco Guzman, a senior policy analyst at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. A recent report co-authored by Guzman found that undocumented immigrants paid a whopping $96.7 billion in federal, state, and local taxes in 2022.

Moreover, advocacy groups worry about the impact mass deportation would have on families. “What does this look like on the ground?” said Liebman, who wondered who would be tasked with enforcing mass deportation, and whether it would require local law enforcement agencies to carry out raids in their own neighborhoods and communities. She noted that the bulk of migrant families across the country are “mixed status” — meaning that some members of a household have documentation while others don’t. “Are we going to go into people’s houses and rip families apart?”

Immigration is the purview of the federal government, and for decades, elected leaders across the political spectrum have failed to pass policies to fix America’s strained immigration system. “It has been very hard to find solutions on immigration reform,” said Gandhi. “And we do have bipartisan solutions on the table. But we just have not been able to get them through.”

Mario Tama / Getty Images

In the absence of other policy solutions — such as addressing the root causes of migration to the U.S. from other countries, including climate change — all-or-nothing imperatives to “close the border” have become popular among conservatives. In fact, a Scripps News/Ipsos poll released last month found that a majority of American voters surveyed support mass deporting immigrants without legal status.

Experts have debated the feasibility of Trump’s promise to enact mass deportations — pointing out that deportations during Trump’s first term were lower than under his predecessor, Barack Obama. (The Biden administration has also enacted considerably more enforcement actions against immigrants than were carried out during the Trump administration.) Although the specific details on how the proposal would be carried out and enforced have yet to be clarified by Trump’s campaign, Paul Chavez, litigation program director at Americans for Immigrant Justice, a nonprofit law firm, is highly skeptical about the likelihood of such a move holding up in federal court.

“I can’t imagine any sort of mass deportation program that doesn’t result in racial profiling of both immigrants and those perceived to be immigrants,” said Chavez. Any form of racial profiling that came out of such an enforcement process would be in violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which effectively prohibits a state from adopting policies that target any person in its jurisdiction based on race, color, or national origin. A mass deportation operation would lead to people being profiled across the country and treated in “a discriminatory fashion based on national origin,” said Chavez — triggering all sorts of lawsuits.

“My sense is that it would be impractical and then impossible to implement in a way that doesn’t inevitably violate the Constitution,” said Chavez.

But whether or not courts upheld mass deportation, the threat of raids would send a strong message to workers, according to Antonio De Loera-Brust, an organizer with United Farm Workers, a labor union for farmworkers that represents laborers regardless of their immigration status. He posited that Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric is purposefully designed to have a chilling effect on U.S. residents without legal status. “The point is not to remove millions, it’s to scare them,” said De Loera-Brust.